Tamara Hinson takes a shine to the unpolished gem that is Naples.

Like this and want more details? Click here to download and save as a PDF.

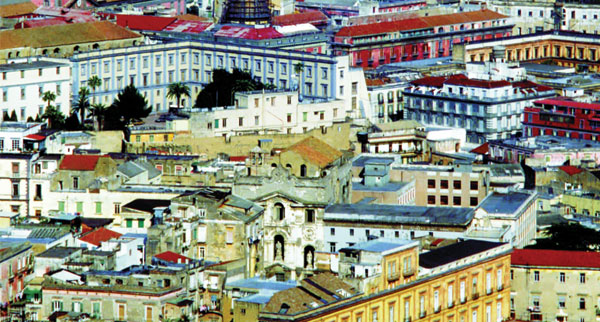

Don’t get me wrong. I love Venice. I adore its refined beauty, network of narrow passageways and gondoliers floating across the lagoon. Naples, on the other hand, is about as far away from Venice as you can get, yet its chaotic beauty is just as appealing.

To start with, I can walk across the city’s main square, Piazza Garibaldi, without having to dodge selfie sticks or risk tripping over the suitcases of map-gazing tourists.

Naples is wonderfully unpolished; peer down any of the narrow alleyways that split off from the main roads and you’ll see laundry loads of clothing hanging out to dry, flapping in the wind, high above small, flower-filled, glass-fronted shrines. It’s a city full of people doing whatever they can to eke out a living, whether it’s a salt-encrusted fisherman shouting out the catch of the day, or a man selling cheap silver jewellery (in one case, beneath a sign that read: ‘imitazione Pandora’. At least he was honest).

The beating heart of Naples is the aforementioned Piazza Garibaldi. The city’s main train station can be found here, along with a semi-subterranean shopping arcade that doubles as a venue for art installations. During my visit enormous, rainbow-hued snails were creeping up the supporting columns.

Equally beautiful are the metro’s dedicated Art Stations, which have been given makeovers by various artists. Toledo station, which was transformed by Catalan architect Oscar Tusquets Blanca, is easily the most spectacular, with high-tech light installations and huge murals covering its walls.

City of churches

But Naples’ most beautiful buildings are the ones with history. It’s a city filled with churches. One of the city’s most spectacular is the enormous Cattedrale di San Gennaro, on Via Duomo. It’s amazingly extravagant with vast expanses of gold leaf and in the crypt’s altar are two vials of blood of San Gennaro.

Legend states that in 1389, the saint’s blood miraculously liquefied after his remains were transferred to Naples. Today, locals come to witness this phenomenon three times a year. It’s believed that if the blood liquefies, it’s a good omen for Naples’ fortunes, while the reverse has been cited as the cause of everything from earthquakes to poor football performances by the city’s team.

But some of Naples’ most beautiful churches are harder to find. When browsing for knick-knacks on Via dei Tribunali I stumbled across the 16th-century Santa Maria della Pace, shaped like a cross, with a beautiful floor made from terracotta tiles. There’s something lovely about stepping from a crowded, chaotic, souvenir shop-lined street straight into the cool, dark interior of a frescoed church. And the restaurant across from the church is where I enjoyed what might just be the best pizza of my life for just €7.

Money matters

Naples is certainly one of Italy’s cheapest cities. If you are planning on checking out its museums, further savings can be made with the Campania Artecard Napoli, which costs €21 for three days and covers admission to more than 40 different sites, including Naples’ Castel Nuovo, a medieval fortress overlooking the ocean. The structure was built in the 13th century and there are daily tours. One of the most spectacular rooms is the Armoury Hall, where a glass floor allows visitors to peer down onto the remains of the Roman villa discovered beneath.

Another Naples gem covered by the card is the National Archaeological Museum, which has the world’s finest collection of Graeco-Roman artefacts.

But Naples is also a gateway city: Capri is just 45 minutes away by hydrofoil or an hour and 10 minutes by ferry, while the coastal town of Sorrento, regarded as the start of the Amalfi coast, is a 50-minute train ride away. Italy’s Intercity train will whisk you to Rome in just over two hours.

But its most famous neighbour is Pompeii, a mere 17 miles away. Most people take the train from Pompeii (Scavi station), but I opted for the bus, paying a couple of euros to hop on a coach from Naples’ seafront bus station. The journey took me past the forested slopes of Mount Vesuvius and past Herculaneum, Pompeii’s sister site.

At the heart of the modern-day town of Pompeii is Piazza Bartolo Longo, a beautiful town square dominated by the Sanctuary of the Virgin of the Rosary of Pompeii (try saying that after one too many Limoncellos). Inside this towering basilica are elaborately painted domes – and more gold. It’s only when I looked a little closer at my photos that I noticed a bride and groom making their way up the aisle behind me. Apparently I’d gate-crashed their wedding.

Back outside, I noticed that above one of the doors is a beautiful mosaic of orange and sunshine-yellow tiles, inscribed with the words ‘Porte della Misericordia’ (Door of Mercy) and a transcription which translates as: ‘anyone who enters through me will be saved’. Perhaps the couple whose wedding I stumbled upon will forgive me after all.

Mosaics and murals

It’s not hard to find the main archaeological site, known officially as the Archaeological Area of Pompeii. The roads which lead to it are lined with stalls selling every kind of religious trinket under the sun – painted figures of the Virgin Mary and magnets, mugs and dishes adorned with religious icons.

I was lulled into a false sense of tranquillity by the clusters of trees that surround the entrance to the site, but upon further inspection, their branches cover long glass enclosures containing the frozen forms of Pompeii’s victims.

Victorian archaeologists realised the voids they found were spaces where bodies had been. As they decayed, the layers of ash solidified around them. Plaster was poured into these empty spaces to create the casts which are now on display.

The eruption took place in AD 79, but there’s still something desperately sad about the frozen shapes. Some are lying down, others folded tightly into sitting positions, as if they are desperately trying to escape the searing heat. One of the most striking images is the form of a young child, the imprint of a nappy-like swathe of fabric clearly visible.

The site itself is huge and several hours are required for a thorough exploration, although its layout, dictated by Pompeii’s original network of streets and squares, makes things easy to follow.

Despite widespread criticism of the government for failing to maintain the site, I was amazed at how well it has been preserved. It holds elaborate mosaics depicting prancing lions and colourful wall murals showing Roman emperors, and at what was once a laundry, I learnt that camel urine was used to bleach robes and tunics, with gallons of the stuff shipped in from North Africa. It appears there was a downside to being a Roman emperor after all.